Flora & Fauna

The coastal path is home to a wide variety of wildlife and plant life. It is particularly important for wintering birds although there is plenty to see, enjoy and photograph throughout the year. Our list of birds on this page may be useful while you enjoy the wonderful wildlife on our doorstep, and if you’re lucky you might spot one of our wonderful coastal mammals. The community of people who are so active on our Facebook page often post beautiful pictures of wild flowers, bees and other insects, so that other people can help with identification.

Mammals

If you stop for a while, and look out to sea you are likely to glimpse both grey and common seals. They haul out and often sing on the rocks off Rockport and Ballymacormick Point.

Otters also fish along the shore and although not as common as the seals, you may see one or more swimming or climbing up on the rocks. Have your camera at the ready.

There is also a chance, on a calm day, you will catch sight of a group of common porpoises.

The land bordering the path is also home to badger, pine marten and bat, although only the dedicated wildlife watcher is likely to see these primarily nocturnal creatures.

Grey Seal

The grey seal (Halichoerus Grypus) is one of two UK species. The scientific name actually means ‘hook-nosed sea pig’ which is likely due to its regal, sloping ‘Roman nose’! Although they are predominantly grey, they are also easy to identify as individuals as they each have distinctive blotches and other markings.

These seals eat predominently fish, squid and octopus.

NI and the UK are extremely important internationally for the survival of the grey seal. Around 40% of the global population breed in the UK. We have a great responsibility to help protect them.

Grey seals in Northern Ireland will give birth to pups from about August onwards, all the way through to winter. It may be tempting to approach the cute white, fluffy pups if you see them stranded on the rocks. But please don’t approach them. They are left for long periods of time while the mum goes hunting. If you feel concerned that the pup is abandoned, please call Exploris on 028 4272 8062.

Pups measure between 2.5 and 3.5 feet, weigh between 12 to 16 kg and must triple their weight on their mother’s milk before being weaned. It is a precarious time for the pups, and many don’t survive, but we can help this by keeping our dogs away from the pups.

Common Seal

The common seal’s scientific name is ‘Phoca Vitulina’. This seal is found in all coastal areas in Northern Ireland, with the greatest density found in Strangford Lough, which is the largest breeding colony in the whole of Ireland. Despite the name, this seal is relatively scarce, with the populations in Northern Ireland being extremely important. In 1988 a breakout of a viral disease wiped out approximately 50% of the numbers in the UK, with the disease striking again in 2002-2003.

This seal is brownish-grey with a mottled appearance. It has a rounded head with a short muzzle and large eyes and is smaller than the grey seal. It is these seals that when they are ‘hauled up’, often lie with their heads and tails raised. Lifespan can be up to 30 years.

Seal Facts

- Seals are known as ‘Pinnipeds’ which comes from the latin ‘pinna’ meaning ‘fin’ and ‘pes/pedis’ meaning ‘foot’.

- The grey and common (harbour) seals found in Northern Ireland belong to the family of ‘true’ seals, characterised by a lack of external ear flaps.

- Seals can dive to impressive depths, up to 5,000 feet.

- Seals can sleep in the water, shutting down their brain activity and rising to the top of the water to breathe without fully waking.

- Seals are apex predators, but this ensures that the marine environment is healthy, and they are also known as a type of ‘sea doctor’ as they remove weak and diseased individuals from prey population, important for healthy evolution.

- Seals are likely to have evolved from an ancestor – Puijila Darwini about 15-20 million years ago, with the closest land-dwelling relatives being bears, dogs and weasels. Because of their close relationship with dogs, diseases can be passed between these species.

Otters

Lutra Lutra

This beautiful creature was close to extinction in the UK from the 1950s to the 1970s. Research undertaken in Cardiff University showed that this massive decline was likely to be linked to chemical pollution. Following the ban of the chemicals responsible, the population has once again increased and we are delighted that they are now a relatively common sight from the North Down Coastal Path, as they are in many coastal regions throughout the UK and Ireland.

This sleek mammal has evolved to be a superb water hunter, with its eyes placed very high on its head so it can still see while almost completely submerged in water. However, they rely far more on hearing and smell than on their eyesight. They have two layers of fur – the equivalent of us wearing a nice fleecy coat with a waterproof coat over it, thus staying toasty warm and dry at the same time.

They can breed throughout the year, and build their ‘holts’ in a variety of places, from within the roots of a bankside tree, to under rocks and rock armouring. Importantly, the otter ensures that it has a variety of ‘escape routes’ from their ‘holt’, with at least one being above water level.

They have a primary diet of fish, but will diversify to frogs and birds if they need to. They cannot hold their breath for very long, therefore do not dive deeply. They have been known to follow the scent of fish upstream and raid garden ponds for fish and frogs!

Insects

Many people come to admire and photograph the insects that thrive on the plants which border the path. We can all help monitor and report the insects we find, by installing and using the FIT Count App on our Smart Phones to record the different species. No expertise is required as the app will ask the depth of each person’s knowledge. Occasionally unusual and rare insects are seen along the path. We always love to see people’s photos and discuss identification. If you are on Facebook, please do share your photos on our page.

It is sad that insects are in such decline on our islands. In Northern Ireland, 3 of our 25 bumblebee species have become extinct, with 8 more at imminent risk. Solitary bees and bumblebees are in serious trouble, and NI is home to many of these. 66% of our moths and 70% of our butterflies are also in long term decline. Our group sees the semi-managed verges of the coastal path as a vital lifeline for insects in our area. Gardens, parks, roadsides and school grounds are all managed almost entirely for the utility of people, in many cases with little regard for biodiversity. This, of course has to change as it cannot continue. Humanity depends on insects as much as the remainder of the natural world, and the balance is tipping. The vast majority of flowers and crops depend on insect pollination.

Another important reason to try to increase our insect populations here, is the importance to the survival of other animal species, such as the tiny Pipistrelle bat, which is totally insectivorous. A great challenge to the survival of our bats is the fragmentation of their habitats, and the associated decline in insects. The deterioration of waterside trees and vegetation is thought to be a serious factor in their reduction of numbers. Bats are frequently seen along the North Down Coastal Path, and just one of many very good reasons to preserve the trees, bushes and vegetation along the verges of our path.

More information on Northern Irish bees and insects, and what we can do to help, can be found on the ‘Buglife‘ Website including this report on threatened bees.

Birds

The shores of Belfast Lough are home to a wide variety of birds. Look out for turnstone searching under stones for food, and listen for the unmistakable cry of the oystercatcher. You may see the aptly named redshank, catch a glimpse of the curved beaked curlew feeding on the shore, or spot a grey heron standing stock still before pouncing on a fish at the water’s edge. You may also see groups of heron in the fields just before the Ballymacormick National Trust reserve as there is a large heronry in the trees over the wall. We have compiled a list of birds you might see along the coastline here.

Along the coastline you should see one of our largest ducks, the handsome , colourful shelduck, whose resident population is increased by winter visitors. Belfast Lough is also a stronghold of the UK’s heaviest duck, the gregarious common eider duck. During the breeding season you will see groups of females with ducklings avoiding the predatory hooded crows. The call of the male during spring would not sound out of place in a ‘Carry On’ film.. listen and you will understand.

In winter you may be lucky enough to spot the scaup, a duck which resembles the tufted duck. Other species you will definitely see along the coastline are the resident reptilian looking cormorant, and shag. Look out for them standing in groups on the rocks around Rockport and Swineley Bay with their wings outstretched

Cormorants on the rocks, photo courtesy of Paul Hunter.

If you take a walk along the Eisenhower pier or the Long Hole in Bangor you will see ‘Bangor Penguins’. We are very proud of our breeding population of black guillemot. When the old North Pier was being rebuilt locals campaigned to have nesting boxes installed. Stop a while and watch our black and white friends.

In Groomsport on Cockle Island in Spring and Summer you can’t miss the nationally important colony of Arctic tern, you will hear them before you see them!

To learn even more about the birds you see, you can refer to our own list of those you may encounter here, or for more detail, visit the RSPB website.

BIRD SPECIES ON THE NORTH DOWN COASTLINE

Click on each bird to find out a little more:

- Bar-tailed godwit

- Blackbird

- Black guillemot

- Black headed gull

- Blackcap

- Black-tailed godwit

- Blue tit

- Brent goose

- Bullfinch

- Chaffinch

- Coal tit

- Common Gull

- Cormorant

- Curlew

- Dunlin

- Dunnock

- Eider

- Goldcrest

- Golden Plover

- Goldfinch

- Great black-backed gull

- Great crested grebe

- Great northern diver

- Great Skua

- Great Tit

- Greenfinch

- Greenshank

- Grey heron

- Grey plover

- Grey wagtail

- Herring gull

- Hooded Crow

- House sparrow

- Jay

- Knot

- Lapwing

- Linnet

- Little Egret

- Long-tailed tit

- Magpie

- Mallard

- Meadow pipit

- Mistle Thrush

- Oystercatcher

- Pied wagtail

- Purple sandpiper

- Razorbill

- Redshank

- Red-breasted merganser

- Red-throated diver

- Reed Bunting

- Ringed Plover

- Robin

- Rock pipit

- Sanderling

- Scaup

- Sedge warbler

- Shag

- Shelduck

- Siskin

- Snipe

- Song thrush

- Starling

- Stonechat

- Swallow

- Swift

- Terns – Common, Sandwich and Arctic

- Treecreeper

- Tufted duck

- Turnstone

- Wheatear

- Whimbrel

- Whitethroat

- Wren

Black-headed Gull

Chroicocephalus ridibundus

One of the most familiar birds that we can see along our coastline, the Black Headed Gull is much smaller than our other common gull, the Herring Gull. This gull is not actually black-headed, but has a chocolate brown hood during breeding season, which fades to small two marks at either side of the head in winter. The UK holds about 6% of the world breeding population, but also has a large resident population.

Black-headed gull facts

- Although the gull is frequently seen on our coasts, it is not actually a seabird, and there are many inland colonies.

- Although we now view this gull as a populous resident, the first overwintering birds were recorded in London just a century ago.

- The Latin name includes reference to the word ‘laughing’ which refers to the distinctive ‘ke-ke-ke’ which can sound like laughter.

Herring Gull

Larus argentatus

This raucous resident is best known for loitering around fish and chip shops, hoping for an opportunistic treat. The herring gull has adapted so well to the urban environment that they can often be found nesting on rooftops and other inventive places, to replicate their natural cliff sites. This large gull has a wingspan of between 1.3 to 1.5 metres. Although the herring gull has a natural diet of fish and invertebrates, they are more than happy to expand their ‘cuisine’ to have a go at pretty much anything.

Herring Gull Facts

- Herring gulls are monogamous and will mate for life.

- They have a potentially long lifespan of around 12 years, but have been known to live up to 49 years.

- A well-known study in the 1950s by Niko Tinbergen was inspired by the red spot on a herring gull’s bill, to ascertain if chicks would take food from any long yellow object with a red spot!

- Although Herring Gulls are thought to be common, it is now known there are many other similar species.

Great Black-Backed Gull

Larus marinus

This gull looks superficially similar to the herring gull, but it is larger, with a darker back and often has a ‘hunched’ appearance when perched. Although we have a small number of residents here, our population mainly consists of winter visitors. The wing span of the great black-backed gull can be up to 160cm, and this huge gull can live in the wild for up to 27 years, although the average is about 14 years.

There are about 17,000 breeding pairs here, but about 76,000 wintering birds.

These birds are not going to be the most popular kid in the playground – as although their diet is very much as a herring gull, eating shellfish, fish and other invertebrates, as well as scavenging from human waste and carrion – they also can be thugs, stealing other birds food, eating chicks and eggs as well as adult birds. The largest gull in the world, an early naturalist spoke of it as follows: “It surely seemed to be a king among the gulls, a merciless tyrant over its fellows, the largest and strongest of its tribe. No weaker gull dared to intrude upon its feudal domain.”

Oystercatcher

Haematopus ostralegus

We are so fortunate that these bold and lively birds are common on our shores. They are distinctive with their black and white plumage and bright orange beaks. True to their name, these birds love eating shell fish, and so our rocky coastline is particularly appealing, with a great supply of mussels, cockles, limpets and similar. Though we will all have noticed collections of Oystercatchers from time to time inland in fields or parks, as these opportunists will also enjoy earthworms, slugs, snails, larvae and even food scraps.

Oystercatcher facts

- Oystercatchers actually don’t eat a lot of oysters, preferring bivalves like cockles and mussels.

- Populations of oystercatchers are very sensitive to reduction in food sources due to the shellfish industry.

- The oldest recorded oystercatcher lived for forty years, one month and two days.

- Oystercatchers are generally monogamous and each pair can be highly territorial.

- They have been known to exhibit ‘cuckoo behaviour’ and lay eggs in other species nests!

Turnstone

Arenia interpres

These protected birds enjoy the stony shores on Belfast Lough. They are a member of the sandpiper family and migrate here throughout the year. They are medium sized, ranging between 21 and 24cm, and are classified as ‘Amber’ under the Birds of Conservation Concern 5: the Red List for Birds (2021). Our shores are of international importance to them, offering refuge on their travels from Northern Europe and also from Greenland and Canada. They are superbly camouflaged within shingle and stones; a small movement will bring your attention to one or two of them, and within a few moments of watching you will become aware of many more in the area – a bit like Magic Eye! They will be mainly seen foraging around rocks and stones for their food.

Turnstone facts

- Although these pretty birds are generally winter visitors, different populations arrive at different times and they can generally be seen all year round.

- Turnstones live for about 9 years, although have been recorded to live till 19.

- Yes – Turnstones do like to eat invertebrates, but scientific literature has recorded a diet ranging from artificial sweeteners to decomposing corpses!

- The UK population of Turnstones tend to breed in Canada or Greenland.

- They will nest in the Arctic tundra, on open ground near water.

- The Outer Ards Special Protection Area (SPA) documentation notes 1210 individuals overwintering and the Belfast Lough SPA (2015) notes 612.

Redshank

Tringa Totanus

The shores of Belfast Lough are immensely important to this beautiful wader, which can regularly be seen along our rocky shores, more commonly a winter visitor but occasionally breeds in Northern Ireland. It is recognisable by its dark orange legs (hence red ‘shank’) eand brown body. It eats insects, small invertebrates, larvae and earthworms, which it prises from mud with its long, narrow beak.

The Redshank features highly on the Outer Belfast Lough SPA (Special Protected Area)

Facts about Redshank

- It is classified as Amber under the Birds of Conservation Concern 6: The Red List for Birds (2021)

- Redshank fly here from Iceland to overwinter in large numbers.

- Redshank make their nest on grassland in wet, marshy areas.

- While most redshank live only to around four years, the oldest recorded redshank lived to be 20 years, 1 month and 15 days.

Curlew

Numenius arquata

This beautiful wading bird is red listed and we are so fortunate to have these locally on our shores. They are Europe’s largest wader, immediately recognisable by their long downcurved bill, which they use for foraging through the mud and silt to reach their prey. The bird has bold streaking and long legs. It is much larger than the similar ‘whimbrel’ which is also a visitor to the North Down Coastline. It has a distinctive bubbling call. The diet consists of invertrebrates, crabs, molluscs. The wintering population of curlews to the UK is extremely important internationally, and sadly the summer breeding population has declined radically.

Curlew Facts

- The curlew’s bill is extremely sensitive and they can sense even a bubble of fear from their prey.

- Female curlew are larger than males and have a proportionately larger bill also.

- Curlews can live up to 30 years, though in the wild most curlews live only about 5 years.

- Curlews move inland or north to breed, where they nest on open grassland.

- The curlew population in Northern Ireland has declined by 82% since 1987.

Lapwing

Vanellus vanellus

The lapwing is a member of the plover family. It is a bird with a distinctive, delicate head and a beautiful long crest. Then in flight, the appearance becomes chunkier, with a blunt wing shape. Lapwing are a fairly frequent sight on the North Down Coastline, sometimes seen on rocks with other species such as oystercatcher and gulls. They are actual a farmland as well as a wetland bird, but will be seen commonly on the coasts in the winter months. Lapwing are red-listed in the UK under the Birds of Conservation Concern and have experienced serious decline, of up to 60%, particularly in terms of our local breeding population. The Outer Ards ASSI includes lapwing as a bird here with a nationally important population. Most of the overwintering population come from Russia.

Lapwing Facts

- Lapwings are unique in the UK in that both male and female sport the crest, and in all seasons.

- Lapwings are also known as ‘Peewits’ which is derived from their distinctive call.

- Lapwings eat invertebrates, small fix, insects, amphibians, but also seed and vegetable matter.

- For the first time for many years, in 2023, two pairs of lapwings raised chicks in County Down, near Downpatrick.

Grey Heron

Ardea cinerea

This wonderful bird is common throughout Northern Ireland, and can often be seen lurking statue still along our rocky shores, waiting for prey. They are frequently seen around the Long Hole or at the Marina, sometimes looking like they are waiting in the queue for the Bangor Boat! They are large creatures, with a wingspan of about 1.8 metres and in flight are slow and ethereal with their curved neck and legs stretched behind them. They mainly eat fish, but are opportunistic and will often visit ponds for frogs, or take small birds such as ducklings and rodents. There are approximately 13,000 breeding pairs in the UK and 63,000 overwintering birds.

Grey Heron Facts

- Herons will often toss a fish and eat it head first, to ensure the scales and fins don’t obstruct the meal!

- Herons next in communities called ‘Heronries’ which are built in tall trees.

- Herons will return to the same colonies time and time again, and some heronries have been in use for over 100 years.

- Herons are proportionally quite light birds, with eggs only the size of a standard chicken’s egg.

- In medieval times, herons were a delicacy with young herons being popular at banquets.

Black Guillemot

Cepphus grylle

Our very own ‘Bangor Penguins’ – these striking little auks have made themselves at home along the rocky shores of Bangor and Donaghadee, nesting in the walls near the piers and on the walls at the Long Hole. These man made structures, to the Black Guillemot, serve the same purpose as their natural homes at the base of cliffs. It has a distinctive black body with red legs and large white patches on the wings. From a distance, it could be confused for a duck, due to it’s habit of swimming on the surface of the water, ducking down to look for fish (they are very skillful swimmers, and are able to stay underwater for several minutes).

Black Guillemot Facts

- This bird is sometimes known as a ‘tystie’ in the Orkney and Shetland, a ‘Scraber’ in Wales.

- Most auks (such as puffins) only tend to lay one egg, whereas Black Guillemots lay two.

- In winter, the birds moult and lose the distinctive black and white features, becoming more grey.

- Although Black Guillemots would tend to live for about 11 years in the wild, they have been documented as living to over 25 years on occasion.

- The Black Guillemot stays close to home, either not migrating at all or going a short distance offshore.

Razorbill

Alca Torda

Like the black guillemot, the razorbill is a member of the Auk family. As such, they are fantastic swimmers, due to their diet of fish. They can be found along our coastlines between March and July where they will nest at the base of cliffs, and rocky ravines. The distinctive bird has the same upright posture on land as a puffin does, and have white faces, with a short blunt bill with distinctive white lines across the end. Razorbills do not tend to breed off the coastlines here, preferring the landscape of areas such as Rathlin, Isle Muck and Gobbins Cliffs, however in Autumn and Winter, the young birds as well as the adults come and feed in the Lough, especially when the shoals of herring and sprat are in. These shoals are badly affected by trawling in the area, having a knock-on effect on these wonderful birds.

Razorbill Facts

- The razorbill’s closest relative was the Great Auk, which sadly is now extinct.

- Razorbills generally hunt about 20m below the surface, but are actually able to go much deeper, up to 140m.

- The average lifespan for a razorbill is 13 years, however the oldest recorded one was 41 years old.

Wheatear

Oenanthe Oenanthe

This distinctive bird is a summer visitor to the UK and Ireland, favouring areas in the North and West to breed. It has one of the longest migrations of any songbird, with some birds (slightly larger than our own breeders) passing across the Atlantic to Northern Spain and West Africa from Alaska and Greenland. It can occasionally be spotted along our coastline, a special treat as the birds can often ‘pop in’ during their migrations.

The male is distinctive, with a blue-grey upper body, a black mask and a white rump with a black ‘T’ on its tail. It is a ground dweller, belonging to the Passeriformes family, about the size of a Robin. There has been some decline in the last decade or two, and the species is now on the UK Amber List of protection.

Wheatear Facts

- The wheatear’s name comes from the Old English for ‘white’ (wheat) and ‘arse’ (ear) referring to their white derrieres!

- The average lifespan of a wheatear is only two years, with the longest known lifespan to be eight years and three months.

- The female is brown in colour and the juveniles are speckled.

- In summer, the bird eats insects, spiders and invertebrates, but in autumn it may eat berries

Terns

Arctic tern – Sterna paradisae, Sandwich Tern Thalasseus sandvicensis– and Common tern – Sterna hirundo

The the three terns likely to be spotted from the coastlines of Belfast Lough are the Arctic tern, the sandwich tern and the common tern. Arctic terns tend to breed in the Northern Isles, (although in 2013, there were 47 pairs breeding in Belfast Lough). They benefit from attention paid to sandeel populations which form an important part of their diet, and are very vulnerable to predation by the American mink. Belfast Lough, the Copeland Islands and Strangford Lough all have healthy colonies of common tern. Common terns breed on shingle beaches and rocky islands, as do sandwich terns.

To the untrained eye, terns are such fast moving seabirds, that identification can be tricky. Common terns are slightly larger, with a long slightly decurved orange-red bill. The Arctic tern’s bill is shorter and redder, which can make the head look smaller and round. The legs of the common tern are longer, and the legs are more orange in colour, whereas the Arctic tern has redder legs. A sandwich tern can be identified by a yellow bill with a black tip and a white forehead with short black legs. The sandwich tern is the largest of the three, about the same size as a black-headed gull.

Terns feed close to the surface of the water, taking small fish which are generally less than 6 or 7 inches long.

Other terns which might rarely be seen off the North Down Coast include the roseate tern and the little tern.

Other facts about terns

- The common tern undertakes one of the most epic migrations of all birds, covering an astonishing 35,000 miles in a round trip each year.

- Tern species will often share the same colonies, which can number between 2000 and 20000 birds.

- Terns exhibit an unusual behaviour known as ‘dread’ in which most breeding birds will silently fly over the entire breeding site for about 20 minutes. It is thought this might be to deter predators.

- The Arctic tern is nicknamed a “sea swallow” due to its tail streamers and streamlined shape.

- Due to the Arctic tern’s migration, they rarely see winter – meaning that they are likely to see less darkness than any other creature.

- Arctic terns engage in an elaborate courtship ritual called a “fish fight” in which the male exhibits his hunting prowess by offering fish to the female.

Red-breasted merganser

Mergus serrator

This native duck is named after the characteristic red breast displayed by the male in breeding season. They are the only species in the genus ‘Mergus’ to frequent saltwater sites, although they breed inland on lakes and rivers. Therefore in winter they can be seen hunting in Belfast Lough which as a site regularly supports nationally important numbers of this bird, forming flocks of several hundred in the autumn.

Facts about red-breasted mergansers

- They are also nicknamed ‘sawbills’ due to their saw-like ‘teeth’ which are helpful for gripping slippery fish.

- They are perhaps not the most popular bird with game fishermen – as they have a liking for salmon and trout.

- The UK wintering population is in the region of 11,000 birds.

Red-throated diver

Gavia stellata

This bird breeds in Arctic regions, and is a winter visitor here. In the winter the bird is plainer, with the characteristic red throat becoming more obvious in breeding season, hence its name. It eats fish, amphibians, invertebrates and weed. They mate for life, with both members helping to build the nest. The waters of Belfast Lough and Outer Ards are extremely important for these birds in the winter, and are classified in the UK as Green under the Birds of Conservation Concern 5: the Red List for Birds (2021). Protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981.

Great Northern Diver

Gavia Immer

This is the largest of the UK divers. It is around 80cm long with a wingspan of 122 to 148cm. They breed in Greenland, Iceland and North America, with some very rare instances of breeding in Scotland, confirmed for the first time in 1970. They are superficially similar to cormorants with large bills and bulky bodies. Although in winter they are generally silent, their call in breeding season is an eerie moan, used in movies to create a spooky atmosphere, but in real life is nothing more than asserting its territory.

The wings of the great northern diver are proportionally quite small, so although once in the air they are strong fliers, it can take some effort to take off. As with other divers they eat a diet of fish and crustaceans, and can dive to great depths for their dinner – up to 60m.

The great northern diver may be seen in Belfast Lough in winter. Over 1,500 birds are said to winter in Ireland and about 4,000 in the UK where they will arrive in October and November and then leave again around April time. In North America great northern divers are known as ‘common loons’.

Black-Tailed Godwit

Limosa Limosa

The black-tailed godwit is protected as a Schedule 1 Species in the UK, with all of the sites in Northern Ireland designated. Belfast Lough and the North part of Strangford Lough are of key importance to this threatened species. For unknown reasons, the population in Iceland has increased, and Belfast Lough provides a perfect environment for their passage and/or overwintering.

Although they will generally be seen in winter here, when their plumage has faded to a greyish brown, their distinctive black and white striped wings will still be evident. These wings are one of the distinguishing features separating it from its close relative, the bar-tailed godwit. They are about 40cm long, although 10cm of this is taken up by the long bill, which is longer in the female than in the male.

The main threats to this bird are loss of the wet grasslands and mudflats on which it depends.

Facts about black-tailed godwit

- Diet consists of insects, worms, snails, small clams, mud snails etc.

- Will feed on tidal mudflats, saltmarsh and wet grassland.

- Belfast Lough is the main site for this bird in NI.

- The last recorded count of breeding pairs in NI was 53. These birds winter in Africa, whereas the majority of our overwintering birds come from Iceland.

- The most common time to see them here is in September and April.

- The typical lifespan is 18 years, breeding from 2 years. The maximum recorded age from ringing is 23 years 3 months and 21 days (in 2001)

Purple Sandpiper

Calidris maritima

This medium sized wader is almost exclusively a winter visitor to the UK, frequenting our rocky shores. There is a very tiny breeding population in a secret location in Scotland and it is listed as Schedule 1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act.

The purple sandpiper is similar in appearance to the dunlin, but slightly larger and plumper, with short legs. It has dark grey upperparts and paler, mottled breast and flanks.

Facts about purple sandpipers

- In flight, the sandpiper shows a dull white wing bar.

- The name comes from the purplish sheen on the upper plumage.

- The purple sandpiper can be surprising tame, and will sometimes be seen on harbours and close to human activity.

- Diet consists of mussels, crustaceans, flies, spiders, winkles etc.

- It has the most Northerly wintering territory of any other shore bird.

- Expected lifespan would be five years, but has been known to live over 20 years.

- The importance of the area to the species is mentioned in the ASSI literature for Outer Ards and the Ramsar for Belfast Lough, with a combined approximation of 9.2% of the Irish wintering population.

Shag

Phalacrocorax aristotelis (Linnacus)

This large black seabird is very similar to its close relative, the cormorant. Indeed, many of us assume that the majority of these birds we see along the North Down coastline are actually cormorants – yet shags here are much more populous. There are in the region of 20,000 breeding pairs in Northern Ireland. The shag is a smaller bird, with a more prominent forehead and sports a crest in breeding season, with juveniles being lighter in colour, with brown above and buff below. Their diet is fish which they hunt by diving from the surface.

Shag Facts

- Shags are extremely courageous defenders of their nests, staying there under attack and behaving menacingly towards intruders.

- Shag nests are composed of rotting seaweed, twigs and other similar materials, put together in an untidy pile and stuck together with shags own guano.

- Shags have an incredible diving ability and have been known to dive in excess of 45 metres.

- The shag is yet another bird who benefits from a healthy sandeel population.

- It is a monogamous bird and both parents share the raising of the 3-4 eggs.

- They are long living – living to a typical age of about 12 years, with breeding commencing at age 4. The oldest recorded Shag was nearly 30 years old.

Cormorant

Phalacrocorax carbo

Cormorants are less populous on the North Down coastline than shags are, but are very similar. They are both large, black waterbirds who can often be seen ‘hanging out’ on rocks with wings outstretched. However, the cormorant is larger than the shag and lacks the crest which can often be seen on a shag. This video taken from the British Trust for Ornithology website gives an excellent account of how to distinguish the two species. The Cormorant is a superb diver and, with short wings, large webbed feet and a large hooked beak is streamlined to catch fish underwater.

Other facts about Cormorants

- The average lifespan of a cormorant is 11 years.

- Cormorants can often be spotted on inland bodies of water, unlike shags who are almost entirely coastal.

- Cormorants’ feathers are not particularly waterproof unlike so many other waterbirds, hence they can often be seen ‘drying out’

- Just like an owl, the cormorant will regurgitate pellets containing bones and undigestible parts of its prey.

Sedge Warbler

Acrocephalus schoenobaenus

This little wetland warbler can be heard sitting in vegetation along the coastal path, singing its heart out in summer. In the field it can seem quite plain, although up close the bold whitish ‘eyebrow’ and darker crown distinguishes it from other local birds. It breeds in reedbeds and marshy vegetation, and one very good reason not to disturb these important areas.

It feeds almost exclusively on insects and other invertebrates.

The male sedge warbler will never sing the same song twice, as the variety of different songs has been proven to impress the ladies!

Dunnock

Prunella Modularis

This dainty little bird is superficially similar to a sparrow. Indeed in the past it used to be known as the ‘hedge sparrow’ – however, it is not in the same family (Passeridae) as the sparrow, and spends much of its time hopping around the ground, foraging for seed and insects, in much the same way as a thrush might. It has a slightly ‘timid’ way of moving, sometimes fluttering its wings, and generally seen alone rather than in groups as sparrows might.

Looking closely, they have a a blue grey head and grey breast, with streaked black and brown upper parts and chestnut on the wings. They have a fine pointed beak, unlike a sparrow which is thicker and more finch-like.

These common garden birds will often make their cup shaped nests in dense shrubs or hedging.

Other Dunnock Facts

- The dunnock is the only UK bird which is a member of the ‘Accentor’ family.

- Dunnocks are scandalously polyamorous. Females will mate with one male, then another, to ensure that her family are well cared for.

- In addition, Dunnocks may mate up to 100 times in one day! A fact that was only discovered in the 1990s.

Robin

Erithacus rubecula (Linnaeus)

No introduction is necessary here. Our sweet little national treasure makes itself seen and heard at every opportunity, gracing twigs and bushes all along the path.

About the same size as a sparrow, the robin has a brown back, white belly and a characteristic bright orange/red breast, earning it the nickname “Robin Redbreast”. It eats a variety of foods, including insects, spiders, beetles, worms, fruit, seeds and nuts and will happily visit feeders to eat suit and fat balls.

Here are a few additional facts about robins, which might interest readers.

- Robins look very sweet, but are in fact very territorial and aggressive with each other and other birds – yet despite this, they will set up home almost anywhere from old containers, rubbish, old coats and any corner of the garden that takes their fancy.

- Robins are very short lived, and although the average is two years, many will perish in their first year.

- It is said that robins follow gardeners around, because they evolved to exploit the holes dug up by wild boar in the woods.

- The Robin’s ‘red’ breast is actually orange, but the word ‘orange’ was not in common use until 16th Century so many birds are named ‘red’ incorrectly!

- They used to be nicknamed ‘Robert Red-breast’ which became ‘Robin’ through the centuries.

- Juvenile robins do not have red breasts, and instead have breasts speckled with dark brown.

Goldfinch

Carduelis carduelis

This gorgeous little finch is so familiar to us here, that we may be forgiven for becoming complacent to its exotic beauty and colouring. It may be seen along the North Down Coastal Path in flocks, delicately picking at thistles and taking the seeds of dandelion stalks and other wild flowers.

It is a smaller finch than our other common finches (chaffinch and greenfinch) at about 12cm long. It has a distinctive red face, with yellow/gold patches on the wings, a black cap, and black around the eyes and wings, which emphasises the patches of colour and white/pale grey.

Other goldfinch Facts

- The goldfinch used to be extensively trapped and used in the cagebird trade.

- The goldfinch is the subject of a well-known painting by artist Carel Fabritius which also gave rise to a recent book by Donna Tartt and subsequent film.

- The collective name for Goldfinches is a ‘charm’.

- Male Goldfinches will enjoy eating seeds of teasel, however female goldfinch beaks are smaller and less likely to reach the seeds.

- Around two thirds of UK goldfinches will migrate to Southern Europe in Winter.

Swallow

Hirundo Rustica

Swallows arrive in NI around the Spring time from their wintering homes in South Africa. They will have migrated approximately 8,000 miles by this stage. They are distinctive, graceful birds – iconic for their erratic, speedy darts, often low to the ground as they hunt for insects. They will favour open ground in areas with water, trees and lots of insects, but may well utilise buildings to build their nests.

Their song is a musical twittering, unlike the shrieking of a swift. They can be identified by their dark bluish backs, forked tails with long streamers and their distinctive red throats, which may not be easily seen when flying.

These birds are amber listed in the UK as there is some concern over their European populations, which may be due to climate change and also modern agricultural practices.

Swift

Apus apus

The common Swift arrives in Northern Ireland from late April to May and generally has left again by late August. They are loud, raucous birds, which can be seen zooming around in towns and cities, calling out. These birds are amber listed in Northern Ireland due to the fact that they have declined by 25% in 25 years. This can be largely attributed to their nesting sites in older buildings having been lost due to having been demolished, or refurbished in such a way that they can no longer access a site. The swift will nest in cracks and cavities in buildings.

The common swift can be distinguished from swallows or house martins by the fact that they are a uniform dark colour, with longer wings and will never perch.

You can help with the effort to monitor and protect swifts in North Down by following the group on Facebook.

Other Swift Facts

- Although swifts now favour buildings in which to nest, they used to do so in high trees. This behaviour is still evident in areas with abundant tall trees such as Scots Pines, in areas such as Abernethy Forest in Scotland.

- Swifts are so airborne that they even mate ‘on the wing’.

- Swifts have tiny feet and legs, yet a healthy Swift should still be able to take off from the ground, contrary to popular belief.

- Despite superficial similarities, swifts are not related to swallows or house martins. In fact they are closely related to hummingbirds.

- Swifts eat about 100,000 insects a day, but with insects declining so rapidly, they are finding it hard to survive.

- Swifts have been known to fly at an incredible 69.3mph.

Reed Bunting

Emberiza schoeniclus

Most of the reed buntings that are resident in the UK do not migrate, although some of the species from Scandinavia may come to the UK to overwinter. The UK population of reed buntings is in the region of 255,000 pairs and as such is not uncommon. However, the population of reed buntings is very sensitive to changes in our agricultural practices and the loss of wetland habitats. Fortunately, many wetland sites in Northern Ireland now have environmental designations such as ASSIs, which allows for a ‘buffer zone’ of wetland fringe vegetation, which is so important for birds such as reed buntings. The combination of grassy areas, rocks, gorse and other vegetation around the North Down Coastline is ideal habitat for reed buntings, which can be commonly seen here.

Reed buntings are small birds, around the same size as a house sparrow. The male in his breeding plumage has a black head and white collar and the female has a buff head and heavily streaked brown underparts. In winter the two sexes are more similar. They have a notched tail with white outer feathers.

Other facts about Reed Buntings

- They are one of only two species of Bunting resident in Northern Ireland. The other is the Yellowhammer.

- They may have two or three broods in breeding season, with four of five eggs in each.

- Their diet is seeds taken close to the ground, and invertebrates, particularly in breeding season.

- The nest is built by the female, often on a tuft of vegetation or in shrubs.

- They are protected under the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order 1985.

Meadow Pipit

Anthus pratensus (Linnaeus)

This streaky bird is widespread throughout countryside and farmland. It has the appearance rather like a small thrush, with speckled breast and a prominent ‘moustache’, with white tail bars. It is abundant in upland areas, and can become quite coastal in Winter – thus is a fairly common sight along the North Down Coastal Path along with its close relative, the rock pipit. Their behaviour can be rather like a lark, flying straight up from grassland while singing loudly. The diet is mainly insects, spiders and other invertebrates, also eating seeds in the winter.

Meadow pipits nest on the ground, concealed within a clump of grass or heather.

Sadly, the meadow pipit, along with so many other birds which favour the country, has been experiencing a steady decline since the 1970s, putting it on the UK Amber list for protection and red-listed in Ireland’s Birds of Conservation Concern.

Other facts about meadow pipits

- Meadow pipits are a favourite host for the cuckoo, despite the huge difference in size.

- They live for around three years.

- They are ‘seasonally monogamous’ birds, finding a new mate each year.

Rock Pipit

Anthus Spinoletta

This little pipit resides around our rocky coasts, feeding on molluscs, invertebrates and seeds among the stones. Slightly smaller than a starling and bigger than a meadow pipit, the rock pipit has olive grey upperparts with black streaks, and grey tail bars.

Rock pipits are resident in Northern Ireland, but some birds also migrate from Norway in the winter.

Breeding starts in March, and the female will build her nest in rocky crevices or hollows on banks. She will use twigs, seaweed and grasses to make a very simple nest which takes about 3-5 days, and then line it with fur or feathers.

Other facts about rock pipits

- A rock pipit may have two or more broods per year with a clutch of 4-6 eggs, however some surveys have revealed that there may be a mortality rate of 65% for juveniles.

- They are raised almost entirely by the female, but the male will guard the territory. However, an usual feature of this species is that, despite being territorial, male rock pipits will join forces with others from neighbouring nests to defend the area from intruders.

- The bird can actually reach speeds of up to 25mph when necessary.

Blackcap

Sylvia atricapilla

Although this little warbler is known as a ‘black’ cap – the female actually has a light brown cap. Otherwise it is a grey bird with brownish grey wings, around the same size as a sparrow (14cm). It is a summer visitor to the UK, filling the air with its beautiful song having spent the winter in Spain and Portugal. However, we do have a small wintering population from birds which breed in Central and Northern Europe.

The blackcap’s diet is a variety of insects and their larvae as well as fruit and berries. Its natural habitat is woodland, shrubs, hedgerows and increasingly found in gardens, where food that is put out for birds is becoming increasingly enticing for these territorial birds. As such, although not a predominantly coastal bird, the blackcap can be seen along the North Down Coastal Path, which borders gardens and contains many trees and shrubs with lots of insects available.

There are around 1.2 million pairs of blackcap which breed in the UK.

Other blackcap Facts

- The blackcap’s beautiful song has earned it the accolade of “Nightingale of the North”.

- The blackcap likes building its nest in thick vegetation such as bramble.

- The oldest recorded blackcap lived for 13 years and 10 months, but typically they would live for about two years.

- Blackcaps are doing really well in the UK and Ireland and populations have increased substantially since the 1970s.

Blue Tit

Cyanistes caeruleus

This acrobatic little resident will be instantly familiar to all of us. The colourful little tit, with its familiar blue and yellow colouring, can form large flocks as it happily comes to gardens to avail of feeders. It will eat insects, seeds and nuts and delight us with its antics. They will nest just about anywhere, including in old boots, lights, sheds and happily will live side by side with humans.

Other blue tit facts

- Blue tits live on average 3 years, although have been known to live till ten years old.

- Most baby blue tits don’t survive their first year.

- According to studies, only 1.2% of blue tits move more than 20km in the winter.

- Apparently, as blue tits get older, they get brighter with each moult.

Shelduck

Tadorna tadorna

The shelduck is protected in Belfast Lough, for which it is cited supports 8.4% of the Irish Wintering Population.

This brightly coloured duck has a bright red bill with a dark green head, mainly white body with a distinctive chestnut brown band around it’s middle. It is found along coastlines where it feeds on invertebrates, small snails etc.

They can be sighted in Belfast Lough throughout the year, but more commonly in Winter when they migrate to Ireland from Northern Europe and also frequently sighted during Spring migration.

Shelduck live for approximately 10 years.

Coal Tit

Periparus ater

This is one of the most common birds in Northern Ireland, often seen flitting around the branches of trees, and boldly visiting garden feeders where it selectively flings unwanted seeds to the ground in search of favourites.

It is a small tit, a bit like a duller version of a great tit, but much smaller. It has a grey tail and grey wings, with some green and white wingbars, a black cap and white cheeks. It has a fair amount of yellow and often forms flocks. It eats seeds, insects and nuts, and nests in cavities in trees, walls and readily uses nestboxes.

Coal tits lay 8-10 eggs and may have two broods in a year. They are short lived, generally only 3 years.

Wren

Troglodytes troglodytes

Believe it or not, this little bird is the most common breeding bird in the UK, with 8.5 million breeding pairs. It is the third smallest bird in the UK, with the Goldcrest and the rare Firecrest smaller again. It is a little brown bird, with a thin beak for eating insects and spider, long legs and a little tail, often cocked as it flits about in bushes and woodland. It has a very loud song.

Other Wren Facts

- The Irish name for wren is ‘Dreoilin’ which means ‘trickster’ – said to originate from an old fable in which the birds were competing to see who would be ‘king of the birds’ and had a race. The Eagle won, and was about to be crowned, when the wren emerged from his feathers, and pipped him to the post!

- Wrens have been about for a very long time, with fossil evidence of their existence from the last ice age.

- Many wrens perish in cold weather, which is probably why they often use bird boxes to huddle and roost in cold weather. Up to 60 have been known to share a single box!

Pied Wagtail

Motacilla alba

This unmistakable little character is often seen along our coastal path. The pied wagtail loves water, and will often be seen bobbing beside streams, lakes and coastlines. Their feathers are black white and grey, with large white tail bars and a distinctive bobbing habit. They will more generally be seen running around on the ground and fluttering close to the ground. This bird is always in a hurry!

The pied wagtail eats insects primarily, but will have a go at anything else from seeds to scraps. There are about 470,000 breeding pairs in the UK.

Other pied wagtail Facts

- The wied Wagtail has many affectionate nicknames, including “Willy Wagtail”, “Polly Washdish” and “Penny Wagtail”.

- It is generally a resident here, but a few birds may migrate to warmer climates in the winter.

- Nobody has yet ascertained why pied wagtails wag their tails continually, but it may be a form of social communication.

- They have a reputation for being imaginative and versatile with where they nest, from gaps in walls, old machinery or simply on open ground.

Grey Wagtail

Motacilla cinerea

Like its close relative, the pied wagtail, the grey wagtail also loves being near water. It is similar in size to the pied wagtail, but has a yellow rump and belly, with a grey upper body. Males have a black bib, which is absent in the female, and females are less yellow on the belly. They love fast-flowing water, but not exclusively and may be seen around stiller bodies of water also. In the winter some birds migrate or move to coastal areas. They nest near water in crevices and hollows and gaps among rocks and stones.

You will commonly see grey wagtails around the stream at Strickland’s Glen.

They eat midges, ants, snails and tadpoles that they find near shallow water.

Other facts about grey wagtails

- The grey wagtail has a much longer tail than the pied or the yellow wagtail.

- In old Scottish Gaelic tradition, seeing a pied wagtail was a portent of bad weather. However, if the grey wagtail was spotted near the doors of houses it would also mean bad weather and furthermore, if the Grey Wagtail were seen between a person and their house, it was a prediction of imminent eviction!

Eider

Somateria mollissima

The eider is a common sight on Belfast Lough, and also possibly one of the more unusual sounds floating across the water. Their call can sound like they are collectively saying “Oooooh” after hearing a naughty joke! The males and females are completely different colourings, and can often be seen in large groups. This bird has a bulky body and is the UK’s largest duck. It has a pale wedge-shaped bill. The male is a distinctive black and white colour, while the females are greyish brown. There are approximately 37,000 breeding pairs in the UK, with approximately 86,000 wintering birds. They feed on blue mussels, molluscs and crustaceans, diving deeply to catch their prey.

Other facts about eiders

- The female plucks feathers from her breast to line her nest. It became common practice for humans to harvest these feathers from the nests after the chicks had fledged. These feathers were so sought after that the eider nearly became extinct in the 19th Century.

- The eider is amber listed on the UK birds of conservation concern.

- A long-lived bird, an eider may expect to live over 14 years, with the longest recorded lifespan being over 35 years.

- Their scientific name means “Softest Down Body”

- Eider swallow their shellfish whole.

- For the 25-26 days it takes to incubate her young, the female Eider does not eat, only drinking occasionally.

House Sparrow

Passer domesticus

This well-known little bird was once the most common in the UK. Sadly its population has declined by over 70% since 1970, which has placed them on the UK Red List for birds. There are many theories for the decline, which is in both urban and rural locations, but one such theory is that the decline was originally coincident with the demise of the horse-drawn carriage and the food opportunities that presented. It is also thought that lead-free petrol may have contributed to insect decline, which the house sparrow relies on for feeding to their young.

House sparrows are sociable and opportunistic, often to be found in flocks and using garden feeders. They have brown backs with black streaks, and the male has a black bib and white cheeks also. Female house sparrows in the field can often be confused for other species of finch – although strictly speaking, sparrows are not finches. Finches will generally be a little smaller than sparrows, with longer legs and a smaller, conical beak. Finches tend to perch higher and be comfortable flying longer distances in the open sky, whereas sparrows hang out closer to the ground, flitting amongst shrubs. Sparrows have longer legs.

Sparrows like to nest in man-made structures, such as under eaves and will readily use nest boxes. They eat grain, seeds, young plants, insects and earthworms, as well as scraps. They are extremely adaptable, living in extremely low and high altitudes, and even breeding in coal mines!

House sparrows can be entertaining to watch. They rarely walk, choosing to hop around the garden, and will be observed taking dust baths. They can be seen regularly on the coastal path and very frequently groups will be seen in the bushes between Skippingstone Beach and Wilson’s Point.

Dunlin

Calidris Albina

This small wader can be seen along the North Down coastline in the winter, sometimes on the rocks beside Seacliff Road, where they may be seen in small flocks with other birds such as ringed plover (as in the photo below).

In the winter plumage, the dunlin is grey above and white underneath with a longish downturned bill. In summer they are easier to identify as they are a dark red above with a black belly patch, however in the winter they are similar to the sanderling, which is slightly bigger. It tends to go to upland areas to breed.

They will eat insects, crustaceans, worms, bivalves, although in the summer it would mainly consist of insects, worms, slugs etc.

This area is extremely important for the dunlin, which winters here in internationally important numbers and as such is mentioned in the literature for Belfast Lough Special Protection Area and in the Outer Ards Area of Special Scientific Interest.

Whimbrel

Numenius phaeopus

The whimbrel is a member of the group, sandpipers, snipes and pharalopes along with birds such as curlew, redshank and turnstone. It has a long downturned bill, very similar to the curlew – but the whimbrel is smaller. The bill is shorter, and straight for the first two thirds, arching downwards for the last third, unlike the curlew which has a longer more curved bill. Whimbrels have a dark stripe across the eye. The whimbrel is neither a breeding nor a wintering bird along our coastlines, but rather stops off for snacks between their Arctic breeding grounds and their West African wintering ground, often in flocks.

The diet consists of crustaceans, crabs and molluscs, as well as insects, slugs and snails, particularly at breeding times.

Facts about whimbrel

- The name ‘Numenius’ for this family of birds is derived from the words ‘new’ and ‘moon’ which refers tot he curve of the beak.

- The whimbrel has been known as ‘May Bird’ in the past due to its appearance in Spring.

Sanderling

Calidris alba

The sanderling may be seen along the North Down Coastline in Winter or in Spring and Autumn as it migrates to and from its Arctic breeding ground. There are approximately 40,000 birds that pass by the UK and about 25,500 that winter here.

It is similar in size and appearance to a dunlin, but has a thicker bill and shows a white wing bar in flight. They can frequent long, sandy beaches, and run with a kind of energetic ‘bicycling’ motion, along the tide line, foraging for insects, marine worms,crustaceans and jellyfish.

Other facts about Sanderlings

- Sanderlings have the unique feature of no hind toes, with front facing toes.

- The oldest sanderling lived till just over 13 and lived in Nova Scotia.

- Although most Sanderlings migrate, some non-breeding individuals will stay in their wintering grounds.

Stonechat

Saxicola rubicola

The stonechat gets its name – no surprises – for the distinctive sound of its call, which some say sounds like small stones being struck together. It can be seen along the North Down Coast, perched on a bush or a signpost, singing its heart out while flicking its wings. The male is quite distinctive, with a black head, white around the neck and an orangey breast. The female will still have the orange tinge but the rest is brownish. They are about the same size as a robin. They eat insects, seeds and fruits, such as blackberries, which are abundant along our coastal path area.

Most stonechats are resident, but some do leave for Europe and North Africa in the winter. They nest near the ground in dense cover – a really good reason why to keep dogs under close control in the more natural areas of the coastal path. They lay 4-6 pale blue/green eggs and may have 2-3 broods per year.

The stonechat is not of any current conservation concern, with around 65,000 pairs in the UK.

Great crested grebe

Although the great crested grebe is primarily a bird which prefers freshwater lakes, it can occasionally be seen along the North Down Coastline availing of the relatively sheltered waters. Indeed, Belfast Lough supports a large number of these birds.

The wonderful crest of this bird is acquired during courtship which includes headshaking and fluffing out of their plumage. It is a large bird, around about the same size as a mallard with a long neck and distinctive white wing bars while in flight. The great crested grebe is a resident in the UK, with a small number of European migrants in winter. There are currently about 4800 in Northern Ireland.

This bird breeds on large, shallow lakes, where they create their nests in floating islands of aquatic vegetation and twigs close to the waters edge. The eggs hatch after approximately 28 days and the little stripy chicks often ride piggy back on their parents backs.

The diet consists mainly of fish.

Goldcrest

This tiny bird is even smaller than a wren, at only about 9cm long – making it Europe’s smallest bird. It is very distinctive and colourful with a yellow/red crown framed by black stripes on the side of the head. It can sometimes be seen flitting among bushes at places along the coastal path, searching for insects, although its favoured habitats would be high up in the branches of coniferous trees, making our beautiful Scots pines a perfect location.

The goldcrest is actually a noisy bird, but it’s call is of such a high frequency that some people may have difficulty in hearing it.

The goldcrest lays about 8 eggs, and the full clutch is frequently about 1.5 times the female bird’s body weight.

Little Egret

Egretta garzetta

This bird, of the heron family, used to be a very rare sight in the UK, but the population has increased substantially in recent years. It is unlike other local birds, being completely white with the upright appearance of the grey heron, but considerably smaller. They have yellow feet, which are used to stir up the mud in shallow water and then extract their prey. It is thought that the yellow feet has evolved to be advantageous in alarming the small prey in the murky water.

There are around 700 birds that breed in the UK, and 4500 wintering visitors. It feeds on small fish and crustaceans.

Egrets were hunted nearly to distinction for their long neck plumes – indeed, it was this decline that inspired the creation of the RSPB in 1889 by Emily Williamson. Now, there are in the region of 1100 breeding Little egrets in the UK with around 12,000 overwintering here.

Linnet

Carduelis Cannabina

This little finch is just slightly smaller than a chaffinch. The female and juveniles are quite similar, which are small, streaky, brownish birds. The male is more distinctive with a ‘pink’ appearance, grey heads, with red/pink foreheads and chests.

Linnets can commonly be seen in and around the coastal path. Although they are primarily farmland birds, they have adapted to a variety of other habitats, including occasionally garden feeders. However, they are happiest in areas with an intensity of seeds, which might replicate the seed-rich stubble of farmland. They enjoy areas rich in hedgerows and gorse, and therefore the areas around the North Down Coastal Path which have an intensity of such vegetation (for example, Seahill or Ballymacormick Point) will also have a higher number of linnets.

Just like so many other bird species, linnets have suffered due to changes to agricultural practices and have declined by 72% since 1967. There are now around 430,000 pairs in the UK.

Linnets are named after their favoured food – seeds, with linseed being the seed of the flax plant, and the latin name ‘cannabina’ referring to Hemp.

They build their nests in areas with native thorny hedgerows or areas rich in gorse. The male is protective of the female – following her around to prevent other males mating with her, indeed spending around 95% of his time with her. The nest is made from vegetable matter such as grass and roots, lined with features and hair. She will raise 2-3 broods in one season.

Linnets are protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981 and classified in the UK as a Red List species under the Birds of Conservation review and as a Priority Species in the UK Biodiversity Action Plan.

Great Skua

Stercorarius skua

The great skua is unlikely to be the most popular child in the playground. A parasitic bully, the skua is known to steal food off other birds, even those much larger than itself, such as gannets. It raids the nests of other seabirds and attacks and eats smaller birds such as puffins. It also will eat carrion, rabbits and rodents.

Although it is similar in size to a herring gull, with a wing span of 124-140cm. it is much more powerfully built. Great skuas are dark brown, chunky in appearance with obvious white wing flashes in flight.

They are not likely to be a frequent sight along the North Down coastal path, and are generally only sighted during migration, as they winter off the coasts of Spain and Western Africa, migrating to breeding grounds in Scotland and Iceland in Summer. There are a very small number that breed in isolated islands in the West and North of Ireland.

These birds are long lived, with an average age of around 15 years but the oldest ringed bird reaching an age of 38. They breed at around 7 years old, with one brood of two eggs, which are tended by both parents. Great Skuas are fiercely territorial around their nests and will gladly divebomb any human who comes too near.

Sadly, in 2022 many great skuas perished in the UK due to avian influenza.

Scaup

Aythya marila

The scaup is a wintering visitor to Belfast Lough. It is extremely similar to the tufted duck and pochard, and really the most skilled birdwatchers will be able to distinguish them due to the subtle differences in colouring and the whiter feathering around the bill. The male ducks have green/black heads, shoulder and breasts with pale grey/white back and white sides. They appear black and white from a distance. Females appear brown, but still have the white patch around the bill, more pronounced than with other similar ducks.

The scaup is a diving duck, hunting mainly at night for molluscs and sometimes larvae (especially in Lough Neagh which is a very successful area for scaup, where they very much enjoy the larvae of Chironomids, the Lough Neagh non-biting midgles.

There are in the region of 6,400 birds which winter in the UK and a very small number which occasionally nest here (in recent years some chicks were raised in Lough Neagh). However, in Belfast Lough, any sightings are almost certainly going to be for migrating species coming here from Iceland or North-East Europe for the winter.

Sadly, in the UK there was a 68% decrease in scaup between 1997 and 2022, making the scaup a Species of Conservation Concern.

Brent Goose (Light bellied)

Branta bernicla hrota

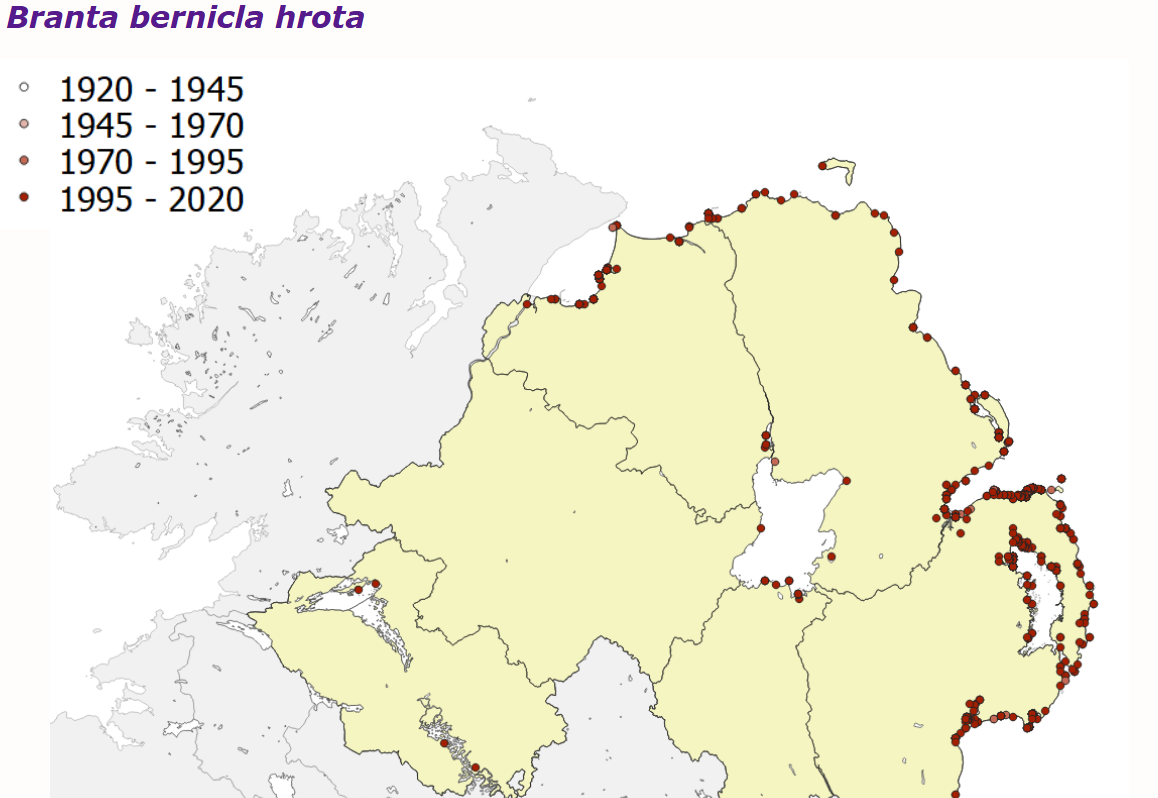

This little goose is not much larger than a mallard, but stockier. The Ards and North Down area is crucial for this species, which migrates from Arctic Canada each year to spend the winters here. In fact, nearly all of the population congregates in Strangford Lough on arrival to dissipate around various sites in Northern Ireland – but the vast majority stay here (see map below).

Brent geese will be a regular site on beaches and estuaries along the North Down Coastline and Belfast Harbour. The geese will feed in estuaries, largely on eel-grass and when supplies grow scarcer in mid-winter will often move to other grassland sites.

The numbers vary from year to year, but number in the region of 30,000.

The goose is quite small and sports a sleek black head and neck with a grey brown upper body and pale grey underbelly. Indeed, the upper feathers are the colour of burnt wood from which its name derives (the old Norse word ‘brandgás’ meaning ‘burnt goose).

These birds undertake an extremely long migration of over 3,000 miles, through Greenland and Iceland before crossing the North Atlantic to get here. This is worth thinking about before we would allow our dogs to chase them while they are trying to feed and rest in the shallow waters.

The average lifespan is in the region of 19 years, but can live much longer (up to 27 years).

Brent geese are highly social creatures, with sophisticated systems of communicating and with specific geese responsible for leading the others (known as ‘compass’ geese). This social activity is important for survival so that the majority of the birds can focus on feeding. Although brent geese will almost exclusively eat eel grass, given the opportunity, they will diversify when need be. In the 1930s a large amount of the eelgrass in Ireland became diseased and died, and the geese had to learn to adapt to eating other vegetation such as saltmarsh and other estuarine plants and grasses.

This area is so important to these birds, which rely so much on us protecting their habitat and as such the brent geese are protected in the Outer Ards SPA under Article 4.1 of the Directive (79/409/EEC).

Hooded Crow

Corvus cornix

This common, sociable corvid is a common sight along our coastline. They will often be seen walking around on the beaches, picking through the stones for crustaceans, shellfish, or basically any snacks they can muster. The hooded crow is an omnivore and also an opportunistic feeder.

The hooded crow is extremely closely related to the carrion crow, and for a long time was thought to be the same species, with hooded crows being more common in some areas and carrion in others. Hooded crows are more common in Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. It is grey in colour with black head, wings and tail. The female is very similar but slightly smaller.

The crows will nest high in trees and buildings and generally have one brood of eggs per year with a clutch of 3-6 eggs which are incubated after about 18 days.

There may be a lot to ‘dislike’ about hooded crows; they steal eggs, young birds, bully other birds and can dominate feeding stations. But it is impossible not to respect and admire them based on their family loyalty, complex structures and extreme intelligence. Hooded crows can recognise humans that are kind to them and remember them, telling the difference between humans that will be a danger to them and those that won’t. They also hold life-long grudges ! They also can share that information with other crows. They also seem to have a lot of cooperation within their family, with younger family members participating with various roles.

Snipe

Gallinago gallinago

The common snipe is a widespread wader in the UK, appearing in many different habitats, as long as there are damp, wet, marshy areas where it can forage. It is medium sized, and a mottled brown colour with shortish legs and unwebbed feet, with a straight, dark brown bill of about 6-7cm in length. It has a wonderful, effective patterning and perhaps the first we might know of its presence is when either one or several of these exquisitely camouflaged birds lurch into flight close to our feet, with a “wisp” – giving rise to their collective noun.

It may be seen on any of our wetland, intertidal areas along the North Down coastline, where it will forage for its favoured diet of crustaceans. It will also eat insect larvae, earthworms, snails etc.

The bird is amber listed in the UK due to a decline in the last 25 years, but we still have in the region of 80,000 breeding pairs and 1 million wintering birds that come from Iceland, Northern Europe or Russia. In courtship, the males make a distinctive noise that sounds a bit like a sheep or goat, giving rise to many nicknames throughout the world (eg “Sky Goat” in Finland). They nest on clumps of dry vegetation within wetland, marshy areas and raise one brood of about 4 eggs between end of April and June.

Their love of murky, swampy areas was the inspiration for the 19th Century poem by John Clare “To the Snipe” which culminates with the verse:

“Thine teachs me

Right feelings to employ

That in the dreariest places peace will be

A dweller and a joy”

Bar-tailed godwit

Limosa lapponica

This bird can be seen along our shores in the winter, traveling from its breeding ground in the Arctic. Some travel further south, and others winter here where it will forage for molluscs, small crustaceans and aquatic insects.

It has long, blue-grey legs with a long bill which is very slightly upturned – pink at the base and black at the tip.. We will not see them in their breeding plumage in which the males sport a red belly and the females are pale orange. In the winter they are generally grey/brown and the underparts are white. It can be distinguished from its close relative, the black-tailed godwit by the barring on the tail (as opposed to the black tail of the latter), the browner, streaked back and the slightly upturned bill as opposed to the straighter bill of the black-tailed godwit.

These birds may congregate in flocks but disperse to feed during the day, in mudflats, marshes and shallow waters.

The bar-tailed godwit is mentioned in the Ramsar designation for Belfast Lough, as this is an important area for these birds, which are present in nationally important numbers. The main threats to this species is habitat loss due to human development, both commercial and residential, changes in agricultural practices and from human disturbance and pollution.

An interesting fact about the bar-tailed godwit is that in 2022 it was tagged and recorded as making the longest non-stop migration of any bird, from Alaska to Southern Australia – a huge distance of 8,425 miles!

Knot

Calidris canutus

This medium-sized wading bird visits our shores in the winter months, favouring sheltered estuaries. They travel from their breeding grounds in northern Greenland, Iceland and Arctic Canada. They are present in Belfast Lough but can be seen in far greater numbers in Strangford Lough – often reaching over 4,000 there.

They are generally seen here in their winter plumage of uniform pale grey, although may start to show some red feathering before they depart in the Spring. They tend to form large flocks and can perform spectacular arial displays, especially in breeding season. They can be very susceptible to dogs and it would be asked that people do not allow their dogs to chase these birds.

They feed on mussels, crustaceans, small crabs etc. which they probe for in the wet sand and mud.

They are amber listed in the UK and their significant areas of habitat here in Northern Ireland have been designated as Areas of Special Scientific Interest and Special Protection Areas.

Bullfinch

Pyrrhula pyrrhula

This striking finch has an unmistakable black head and tail, a pink/red breast which is brighter and more defined in the male, while the female is slightly duller. It is a bulky bird (hence the name) with a short, thick beak.

They are notorious for eating buds from fruit trees, whilst also eating shoots, flowers and seeds.

Despite their name and appearance, they are actually very wary of humans and less likely to visit feeders in gardens than some other birds, with only 10% of gardens reported as having them. If you want to attract them, then planting a fruit tree would be a great place to start!

They generally nest in conifers or other dense vegetation, a few metres above the ground. They lay between 4 and 6 eggs between May to June. They are mainly resident here, but occasionally may migrate south for the winter. Here in Northern Ireland, they are more numerous in the west, however they are occasionally seen along the coastal path. They are listed as a UK Priority Species and red-listed as a Bird of Conservation Concern (BOCC). As with other birds, recent declines are likely due to intensification of farming, removal of trees and hedgerows and over-management of existing hedges.

Chaffinch

Fringilla coelebs

This widespread finch is common throughout the UK, and likewise will be a common sight along the coastal path.

The male is more recognisable than the female, with its terracotta coloured breast, deep brown back and contrasting blue-grey head. The white wingbars stand out in contrast with the black feathering on the wing and the other colouring. The female is a little duller in comparison and in the field can look rather like a female sparrow. She is, however, quite different with a greenish back and grey underparts. She also has white wing bars, but they are less obvious than the males, being narrower and with less contrast.

There are about 6.2 breeding pairs of chaffinch in the UK, which are found in a variety of habitats. They will happily visit feeders to eat seeds, nuts and fruit – and also eat insects and caterpillars. The female chaffinch builds her nest made of vegetation such as moss and grass, with feathers and may even bind it with spider’s webs, before lining with wool and adding camouflage in the form of bark. They will often have more than one brood in a season consisting of between 2 and 8 eggs.

Interestingly, the name ‘coelebs’ means ‘bachelor’ and is derived from the tendency for chaffinches to form all male flocks!

Common Gull

Larus canus

The common gull is similar to a herring gull, but smaller with a daintier yellow bill. Its legs are greenish in colour and its bill generally lacks the red patch under the bill that the herring gull sports. Despite its name, it is not really common.

The common gull, like its larger counterpart, is a scavenger that eats pretty much anything, from carrion, small mammals, rubbish as well as insects, worms and fish. There are about 49,000 breeding birds in the UK and around 700,000 wintering birds which, in Ireland tend to come from northern Scotland and Scandinavia. They breed on islands and cliffs and are amber listed in the UK under the Birds of Conservation Concern.

Common gulls may live up to 20 years old.

Golden Plover

Pluvialis apricaria